Pirates and redcoats, Quakers and socialites: all are part of the past in Jamestown, Rhode Island, which is surrounded by history as surely as by the waters of Narragansett Bay.

The town of about 5,400 residents a mile west of Newport is situated on Conanicut Island, nine miles long by one mile wide, the second largest island in Narragansett Bay, and named for the Narragansett sachem who permitted English settlers to graze sheep on the island in 1638. Ferry service between Conanicut and Newport was in operation by 1675, and by the late 19th century, when Newport had become a summer haven for the wealthy, the agricultural island town of Jamestown had become a destination for day trips and summer vacations.

“We’re full of stories!” exclaims Rosemary Enright, president of the Jamestown Historical Society, adding, with a laugh: “Nobody knows how much is true.” Ms. Enright has written extensively on local history.” Her books with co-author Sue Maden include Jamestown: A History of Narragansett Bay’s Island Town and Legendary Locals of Jamestown, and the duo pen a monthly column on local history for the Jamestown Press.

At Antique Homes’ invitation, Ms. Enright described three of her favorite old houses in Jamestown — plus a windmill.

“A lot of our homes are from the late 19th century, when Jamestown became a destination,” she said. “Many of the homes on Jamestown were burned down during the American Revolution, when the town was occupied by the British. All of downtown was burned out.

“Probably the oldest house on Jamestown is one called Cajacet. It was built by Captain Thomas Paine, spelled exactly the same way as the Revolutionary War writer, but not the same person. The ownership of the land was transferred to [him] in 1694-95.

“He was a privateer. After he stopped being a privateer he came and settled on Jamestown and built a house overlooking the water at the north end of the island. He was a friend of Captain Kidd’s — they, shall we say, worked together. Stories about him include the [one] that Captain Kidd left his treasure with Captain Paine when he went up to Boston and was arrested there, and that it was buried on-site. No one has ever found it.”

Cajacet, at 850 East Shore Road, is known alternately as the Thomas Paine House, and dates to the 1690s. Built as a two-story house, with a large room on each story, it was enlarged and altered at least twice in the 18th century, and again in 1882, 1915 and in the recent past, according to Historic and Architectural Resources of Jamestown, Rhode Island, published by the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission in cooperation with the Jamestown Historical Society.

“It was owned for quite a while by the Vose family, who ran the Vose Gallery up in Boston,” Ms. Enright said. “They did a lot of renovation on it, but it still looks pretty much the same. It’s a lovely house, too. It still has Thomas Paine’s tombstone in the front yard.

“There’s a story about the treasure. When they were redoing it in the 1950s, a group of workmen were digging in the yard, working on sewerage or something of that nature. They didn’t come back the next day and disappeared from the island. When people went looking at what they had been doing they found one gold coin.

“Whether any of that is true…,” she said, with a laugh.

“The Carr Homestead is still owned by the same family that built it and owned the property since 1657. The house itself was probably built about 1776 although some of it is probably older than that — it’s always hard with those houses when they’ve taken them apart and put them back together again.

“The family were Quakers and they stayed on the island during the British occupation. During the Revolution the population of the island went down to about 350. Nicholas Carr was a Quaker and according to family lore, when one of the the British officers came around and told him to stop working in his field, he just ignored the order. And he was hit over the head. So he just dragged the British officer off and beat him up.

“His great-great grandfather was Caleb Carr, who was one of the original signers of the purchase agreement to buy Jamestown and one of the men who actually recommended that the town be made into a township. He was drowned in 1695 traveling on Narragansett Bay on one of his own ferry boats. This is one of those stories that I’ve never been able to track down: According to Indian lore, he was actually pushed overboard. The other story was

that he was floating barrels of liquor and he fell overboard. He was in his eighties — I’m not exactly sure I believe that one! Anyway, he did drown.”

Historical and Architectural Resources of Jamestown, Rhode Island describes the Carr Homestead, at 90 Carr Lane, as “a two-and-a-half-story traditional early Rhode Island farmhouse, with a large, brick, center chimney, shingled sides, and a central entry, with transom lights, in a five-bay facade” on a lot that includes “a corn crib, sheds, and fine stone walls.” Established as a farm, the property continued in agricultural use well into the 20th century.

“Known affectionately as ‘The Homestead,’ this farmhouse has been a gathering place for many generations of Carrs,” the guide continues. “It is presently owned by the Carr Homestead Foundation, which makes it available to Carr descendants for summer vacations as a means of preserving family traditions and acquainting younger generations with their ancestors’ way of life.”

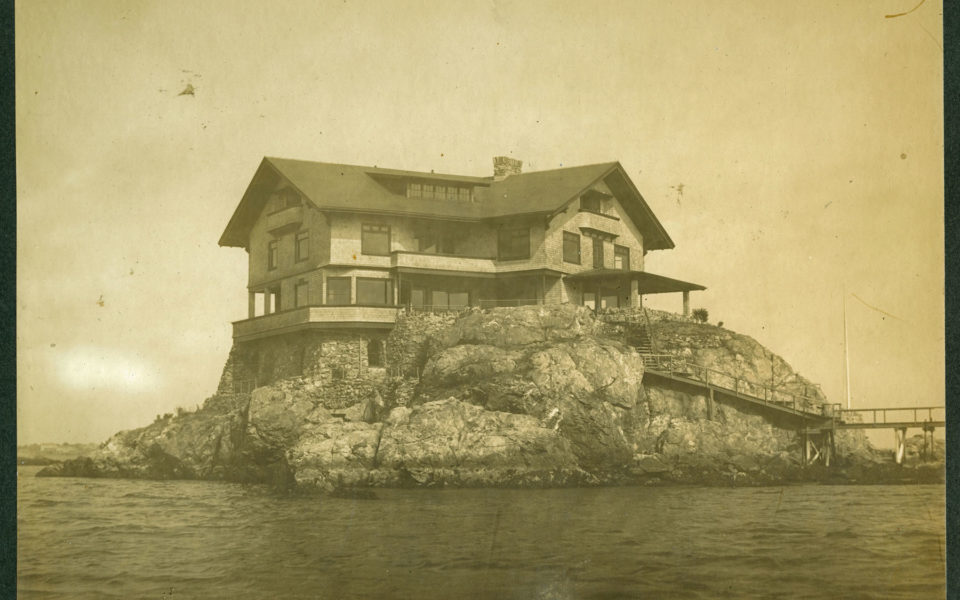

One of Jamestown’s most well-known houses is Clingstone, which actually sits on a rock off the coast, Ms. Enright said. “The house fills almost the whole rock. It was finished in 1905. It was built by J. F. Lovering Wharton, of the Wharton family — we had a lot of Philadelphia people on the island.

“He had owned a house on [Jamestown]. It was a beautiful house overlooking the water where Fort Wetherill is now. When they decided to build Fort Wetherill they took his house [by eminent domain]. They used it as officers’ quarters for a while, then destroyed it. He was so mad he decided he was going to build a house the Army would never want. So he built it out on this rock, just off Fort Wetherill.”

Clingstone perches atop a rock in an island group called the Dumplings in Narragansett Bay. “Built on a very grand scale, this overgrown bungalow-chalet rises three-and-one-half stories to intersecting chalet-like gable roofs,” according to Historical and Architectural Resources of Jamestown, Rhode Island. “The building’s structural system is heavy mill-type framing, overdesigned to withstand hurricane force winds. Clingstone is shingled inside as well as out, the ruggedness of the interiors enhanced by massive beachstone fireplaces and burlap-covered ceilings. Picture windows offer views in all directions, and in order to eliminate the need to open the heavy plate-glass windows, the rooms are provided with ventilating hatches built into the walls.” Enright said: “It went through the Hurricane of ’38. Some of the rock was washed away but the house survived. It fell into rack and ruin in the ’40s and ’50s, then a gentleman who was related to [the Whartons], by the name of Henry Wood, bought it in 1962 and brought it back. He put in it wind power and toilets that don’t send things out into the bay. It’s got cisterns for water and all kinds of modern conveniences out there now. It’s a lovely, lovely place to visit.”

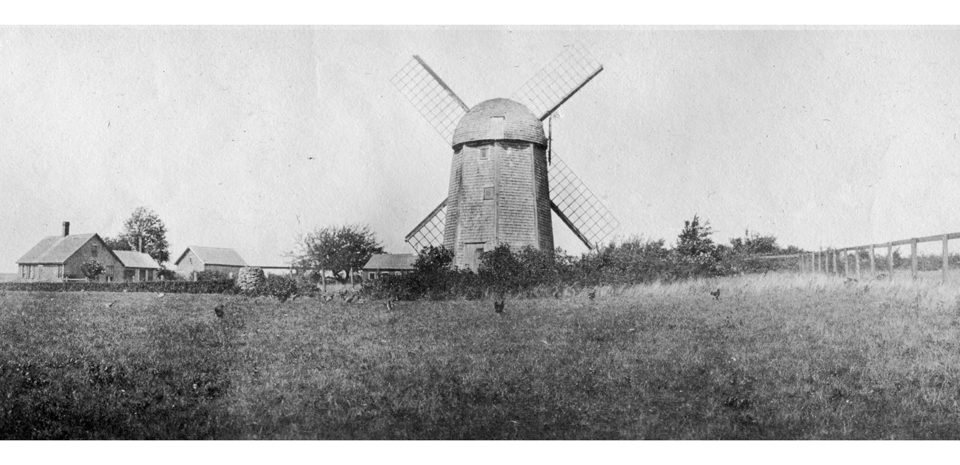

And now, the windmill. Built in 1787 and in operation until 1896, the landmark Jamestown Windmill stands atop Windmill Hill in the center of the island, according to the Historical Society, which has an image of the mill on its seal. The three-story octagonal structure’s domed bonnet holds the sails and can turn to capture the wind from any direction. The original framework of the mill is made of hand-hewn chestnut timbers, while the exterior is sheathed in cedar shingles.

The mill is maintained in working condition. On Windmill Day, held every even year, the cloths are raised on the sails and the bonnet is turned so the sails catch the breeze. The next Windmill Day is in 2016.

“The windmill is one of those structures that was built directly after the American Revolution because of the British depredations,” said Ms. Enright. “It was built in 1787, on land that had belonged to a Tory — originally it had belonged to the governor of Massachusetts and then it was owned by the deputy governor of Rhode Island, both of whom were Tories.

“After the Revolution, the island became very isolated because Newport also had been destroyed by the British and it had been the mainstay of where we would send our produce [as] a farming community. They asked the state if they could have some of the land that had been confiscated from the Tories. The state gave them that land on the grounds that they build and maintain a windmill that would grind the grain for the island. And they did. They built it right away within the year, and a little house next to it that was used by the miller.

“The mill was used primarily to grind what they called Indian corn, a form of corn that comes off the stalk dry. It was used by a series of millers from 1787 to 1896, when the quicker grinding done by steel mills out in the Midwest was making local mills outmoded.

“It was derelict: it was just standing there and nobody wanted it. [An effort to save the mill was launched by] a bunch of Jamestowners. At that point, the town was more than double the

population in the summer that it was in the winter — it had about 1,000 people in the winter and 2,500 extra in the summer. The ones that led [the campaign] were the summer Jamestowners — to the year-round Jamestowners the windmill was something that had been around forever, but for the summer Jamestowners it was picturesque.

“Both summer- and year-round people contributed. They bought in in 1904. The Jamestown Historical Society was formed in 1912 and took over the responsibility and still takes care of it. We have it open on weekends during the summer and also whenever any group wants to go through, we take them through at any time.

“One of the really interesting things about the windmill is that it is the only windmill in Rhode Island, and as far as I know, the only one in New England that is in the same place that it was built. It’s on the top of a hill. It’s got a gorgeous view. If there weren’t trees you could see both sides of the island…From the windmill you can see the Newport Bridge and almost all the East Passage and the Naval War College.”

Ms. Enright, who has lived in Jamestown for a little more than 40 years, was asked to describe the appeal of the island community that has captured her so.

“I moved up here when I got married, to a gentleman who was a summer Jamestowner for four generations,” she said. “When we got married, neither of us had jobs, so we came to Jamestown. We just sort of settled in.

“It’s quiet. I’m not quite sure why I like the quiet — I spent 12 years in New York City before I moved up here.

“It’s a town of really nice people. It’s a town that tries to keep its rural character even though it’s constantly having to grow, because people want to live here. The people who move in generally end up becoming part of the town and trying very hard to keep it what it is.