A Brief History of the American Doorknob

“Ode to a Doorknob” – singing praise to such a simple everyday object, sounds bizarre and ridiculous, doesn’t it? Well, that is exactly what many old home magazines have been doing in the recent years. Unfortunately, they have been narrowly focused on the decorative “Victorian Era” hardware. For sure, with the possibly of as many as 5,000 decorative doorknob designs created during this period of American Builders’ Hardware (from late 1860s to early 20th century) is indeed rich, interesting, and enjoyable to study. The Victorian period was the height of hardware’s use as decorative art. Antique hardware has become not only an interest to the old home restorer, but a major field in collectibles. The historic and aesthetic value of antique hardware was recognized by a group of people in the 1970s, which organized as the Antique Doorknob Collectors of America in 1981, a nonprofit whose purpose is the study and preservation of ornamental hardware. They are constantly working to enlarge their research archive of hardware catalogs and advertising material, and updating their reference book “Victorian Decorative Art,” which documents decorative doorknob designs of the period previously mentioned.

So, what about the earlier hardware, which a good number of us in the Northeast living in homes dating before 1860 might have or had in them?

So, what about the earlier hardware, which a good number of us in the Northeast living in homes dating before 1860 might have or had in them?

I myself have chosen to live in and restore an early 19th century house and must decide with what I am going to replace the cheap hollow doors with their non-descript brass plated doorknobs installed in the 1960s.

With an acute interest in the early years of our nation, its transition from a colonial economy to an industrial economy and its search for national identity, I have been studying our industrial revolution and early architectural styles. Since 1998, I have attempted to put the pieces together to reconstruct the history of the American Builders’ Hardware Industry and its place in our industrial and material culture history, in this article I will now recount briefly to you what I have found and concluded to date.

First of all, the house is simply “a machine for living,” a structure that gives you shelter, security, and emotional well-being, a.k.a., “Your Home.” Builders’ hardware such as hinges, latches, locks, doorknobs are the components of that machine, which make it functional and allow you to obtain the fore mentioned requirements of life. Secondly, to the old homeowner, Builders’ hardware is a very important part of the house’s heritage, because it is one of the most significant elements of its creation. Hardware, as stained glass and decorative woodwork, often referred to, as pieces of “House Jewelry,” were functional ornamentation used by the original builder/owner to beautify their home and to impress their houseguests.

First of all, the house is simply “a machine for living,” a structure that gives you shelter, security, and emotional well-being, a.k.a., “Your Home.” Builders’ hardware such as hinges, latches, locks, doorknobs are the components of that machine, which make it functional and allow you to obtain the fore mentioned requirements of life. Secondly, to the old homeowner, Builders’ hardware is a very important part of the house’s heritage, because it is one of the most significant elements of its creation. Hardware, as stained glass and decorative woodwork, often referred to, as pieces of “House Jewelry,” were functional ornamentation used by the original builder/owner to beautify their home and to impress their houseguests.

As to an actual restoration project, I would like to quote the late renowned blacksmith historian, Donald Streeter, “To accomplish a successful restoration, the restorer seeks to use hardware, which is historically correct and functional, never self-consciously quaint or artificial.” Thus, in a true restoration project, there should be a close relationship between the hardware and the building’s architectural period detail; the hardware should be as authentic as the architectural reconstruction. Conscious research in the area of hardware can make the difference between a “renovation” and a true “restoration.”

is historically correct and functional, never self-consciously quaint or artificial.” Thus, in a true restoration project, there should be a close relationship between the hardware and the building’s architectural period detail; the hardware should be as authentic as the architectural reconstruction. Conscious research in the area of hardware can make the difference between a “renovation” and a true “restoration.”

Since the formulation of the idea of grasping a round object to open a door, doorknobs have been the subject of technical development and artistic expression, taking on many shapes and ornamentation and made in various materials; glass, metal, clay, porcelain, wood, plastic and other contrived compositions.

Since the formulation of the idea of grasping a round object to open a door, doorknobs have been the subject of technical development and artistic expression, taking on many shapes and ornamentation and made in various materials; glass, metal, clay, porcelain, wood, plastic and other contrived compositions.

With all of this in mind, we need to first look into the history of American Builders’ Hardware from Colonial times to 1860.

Early American Builders’ Hardware Industry

Dating of hardware is often quite difficult, particularly with the early wrought iron pieces. Historically most hardware before the mid-19th centuries came from England. In fact, it has been claimed that as late as 1838, ninety-five percent of hardware used in America was imported from Europe. This means that contrary to the long time myth, the assumption that the majority of our early builders’ hardware and nails were made by local blacksmiths is false. Actually, our early blacksmiths produced very little during and immediately after our Colonial period. Their few existing account books do confirm that they mostly repaired iron items and occasionally made nails and some latches and hinges.

Reason being, that as a “British colony,” America was discouraged from manufacturing finished goods, which could compete with the motherland’s manufacturers and merchants. The colonies were expected to supply the raw materials (i.e., wood, iron, and cotton)o England, and later to purchase the finished products made from them. To prevent the development of manufacturing in her colonies, the British government instituted and attempted to maintain restrictive measures on our domestic production, except for simple “made in the home” goods.

The British Government also passed laws to prohibit the exportation of machines or their models and established the policy prohibiting skilled English craftsmen from leaving the country. England intended to be the most advanced industrial nation in the world from which others would have to buy manufactured goods.

Secondly, contemporary newspaper advertisements, ships’ cargo lists showing imported goods, and the surviving late-eighteenth-century hardware catalogs from Sheffield, England hardware manufacturers provide convincing evidence that Colonial builders’ hardware was almost exclusively exported from England. Lastly, this presumption is confirmed by the fact that period hardware, such as hinges, latches, and locks appear in identical physical form throughout the entire original thirteen colony-states.

It was not until 1815, after the American Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars (1799-1815) and co-existence War of 1812, did America finally “shed the yoke of colonialism.” Thirty years after declaring its independence, America finally starts to sever its historical, cultural, and economic ties to its former motherland and pay more attention to the internal development of the “United States of America,” by facing its deficiencies to become truly self-sufficient. Whereas, as its shipping trade had been interrupted by the wars and the consequential trade restrictions, as the Embargo Act of 1807, manufactured goods had been difficult to get and were expensive. America set out to build its own manufacturing industries to provide the needed products. The new nation entered whole-heartily with the spirit of innovation and capitalism into the Industrial Revolution. Americans soon demonstrated a great talent for mechanization, transforming their agricultural and trade-rooted economy into a more balance economy with an industrial partner.

The U.S. Government aided the enfant industries by placing high tariffs on imports as a protective measure and as an attempt to make domestic made goods more price-attractive.

Lastly, the fact that the early patent records from 1790 to 1836 held at U. S. Patent Office were destroyed by fire in December 1836, makes early hardware research a challenge.

Industrial Revolution in the 19th Century

Between 1820 and 1860, the American Industrial Revolution gained great momentum, shifting production from “made in the home” to the factory. The basic principle of the Industrial Revolution can be defined as “man’s desire to extend human physical capacities and economic resources by making less labor do more work.” The invention of machines designed to accomplish a specific task” – reduced human physical work and time required to complete a task. This permitted increase production with the reduction of production human labor costs, making the products more standardized and profitable than the “hand-made.”

The tremendous growth of our industrialization was made possible by the improved means of transportation, increased population, and inventions. Transportation systems; canals, steamboats, and railroads, brought the raw materials to the factory and carried off the manufacture goods to various parts of the country. The increasing population (between 1812 and 1852, the population increased from 7.25 million to more than 23 million) supplied the necessary labor force; many were the newly arrived immigrants, but the larger labor supply was the native-born women and children who took up employment in the factories. There was a great influx of people from the farms into the cities and factory towns, who sought a better economic life. The census of 1860 shows that one million three hundred thousand people were working in factories and shops, producing nearly two billion dollars in manufactured goods. Also, at this time, the infamous “Yankee Ingenuity” came into play, inventive Americans were arriving at many new ideas to create and improve machinery by making it work faster or smoothly or more safely. Between 1850 and 1860, thirty-six times as many patents for inventions were issued every twelve months as had been issued each year before the War of 1812.

Within four decades after the American Revolution, the young nation of the United States found itself in a period of unprecedented growth and transition. Domestic industries would have to meet the needs of its rapidly growing population that was expanding westward, extending the country’s boundaries far beyond the original thirteen colonies hugging the Atlantic coastline, as far as Michigan and Wisconsin (between 1812 and 1852, the country expanded from 4 million square miles to 7.8 million). The subsequent housing boom required a large amount of architectural hardware. By the 1830s, America had an emerging builders’ hardware industry in the Northeast, composed of small entrepreneurships located in the major cities, such as New York, Philadelphia, and Boston, and in the new factory towns as New Britain & New Haven, Connecticut, which had to supply the hardware to make the new buildings operational. As the other infant American industries, it encountered much difficulty during its early years. The lack of machinery and tools prohibited completion with imports; early products were costly and were regarded by the handmade market as inferior to factory-made imports. The companies had to either buy or to design and fabricate their own patterns, machinery, and tools to make the products that the growing housing market demanded.

As descriptions of new machines and processes appeared in print, Americans eagerly read about them and created their own versions of the inventions being invented in Britain. Although the British Government attempted to prevent skilled mechanics from leaving Britain and advanced machines from being exported, these efforts mostly proved ineffective. Americans worked diligently to encourage such transfers, even offering bounties to entice people with knowledge of the latest methods and machinery to come to the United States.

Utilizing the mechanical power generated by water wheels and the newly developed steam engine, and the newly invented machines, America moved out of the “Age of Wood” into the “Age of Iron”. Subsequently, the builders’ hardware industry progressed greatly between 1830 and 1860, using the new power sources, new production methods, machines, and tools.

Similar to today, there were periods of economic woe. The most serious were the “Panics of 1837” and “1857,” times of over-optimism, both people and businesses living beyond their means were suddenly confronted with an economic crash. Businesses were forced to stop buying and manufacturing things, because they could not sell them. Many companies failed or had to make great sacrifices. This drastic slowdown cost thousands of workmen to lose their jobs. Businesses went in default on the investment loans, causing the banks to shut their doors. As a result, for a number of years after, the nation was shrouded with dark anguish – the economy “on the rocks,” factories, stores, banks suffering and massive unemployment.

Success in establishing large-scale hardware manufacturing in the U.S. did not come about until the later half of the nineteenth century. Only after inventing new methods of manufacturing and improving iron/steel production were they able to create a stable and efficient position to meet the domestic demand and start to export to other countries.

The 1820s and 1830s were the early years of experimenting with mortised door fastenings (i.e. latches & locks).

Pre-1840 Builders’ Hardware

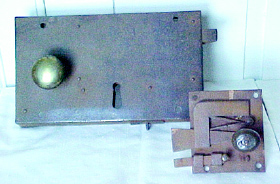

Most of the hardware used through the Colonial period and well into the second half of the nineteenth century was of English origin. An early simple Greek Revival building might still have had 18th century-style, hand forged “H” and “H&L” hinges, Norfolk thumb latches, surface-mounted box lock, a.k.a., “rim” lock, and spring latches. The doorknobs of this period were the small, elegant English style lathe-turned hand-finished brass that operated spring latches and box Locks.

Most of the hardware used through the Colonial period and well into the second half of the nineteenth century was of English origin. An early simple Greek Revival building might still have had 18th century-style, hand forged “H” and “H&L” hinges, Norfolk thumb latches, surface-mounted box lock, a.k.a., “rim” lock, and spring latches. The doorknobs of this period were the small, elegant English style lathe-turned hand-finished brass that operated spring latches and box Locks.

Whereas more ambitious buildings might have had the advanced hardware, such as, cast iron butt hinges (an English patent in 1775), more sophisticated box or rim locks (i.e. Carpenter or Young). Cut nails and pointless wood screws replaced the earlier wrought iron nails as builders’ fasteners.

Mortise locks had been made in England since around 1790, but were not largely used in America until 1840s. This was due to the narrow thickness of the doors in the majority of Colonial period houses. Being 1¼” or less, the doors could not be cut out or mortised to accept such locks. These thin doors were usually equipped either with surface mounted thumb latches, spring latches, or rim locks. Then during the1820s/30s, common interior doors started to become thicker (1½”, 1¾”, 2″), which allowed them to accommodate a mortise lock or latch. The latches pictured are ingenious apparatus invented by the Blake Brothers, nephew of Eli Whitney, of New Britain, Connecticut, which were mortise cylinder latches patented in 1833, using a concept that would not be universally accepted until the 1940s.

The first American metallic doorknobs which appeared in the 1830s, were heavy foundry cast brass knobs. They were mushroom-shaped, spread-foot knobs and not as refined as the earlier English lathe-turned hand-finished brass knobs. They were very likely first made by the North & Stanley Co. in New Britain, Connecticut.

With the invention of a glass-pressing machine, patented in 1826, permitted the manufacturing of inexpensive and mass-produced glass articles.

Furniture and door knobs were the first items made by the pressing process. Thus, the pressed glass doorknob was the very first doorknob made in America and the first truly original decorative doorknob. These early pressed glass doorknobs, were simply a large furniture knob, mounted by insertion of a hand-wrought spindle through a pierced hole in the glass. The knob was then secured with a brass nut to the spindle. These knobs were fitted with brass ferrules, to prevent damage to the base of the glass knob. The ferrule fitted into a brass rose, which acted as a bearing plate, preventing wear on the door’s surface by the turning of the doorknob.

Furniture and door knobs were the first items made by the pressing process. Thus, the pressed glass doorknob was the very first doorknob made in America and the first truly original decorative doorknob. These early pressed glass doorknobs, were simply a large furniture knob, mounted by insertion of a hand-wrought spindle through a pierced hole in the glass. The knob was then secured with a brass nut to the spindle. These knobs were fitted with brass ferrules, to prevent damage to the base of the glass knob. The ferrule fitted into a brass rose, which acted as a bearing plate, preventing wear on the door’s surface by the turning of the doorknob.

Next, in 1837, was the first patent awarded for “applying a glass knob to a metal socket.” The knob was held in the metal socket that allowed the knob to be attached to the spindle by a small pin. The knob was once again mushroom-shaped with an attractive brass step-tapered shank. This design of the socket/shank became the long time standard for glass doorknobs manufactured until 1915. The two patents, the pressed glass process and the brass socket were inventions patented by Enoch Robinson of Boston, who would continue to make a great impression in the hardware industry.

Next, in 1837, was the first patent awarded for “applying a glass knob to a metal socket.” The knob was held in the metal socket that allowed the knob to be attached to the spindle by a small pin. The knob was once again mushroom-shaped with an attractive brass step-tapered shank. This design of the socket/shank became the long time standard for glass doorknobs manufactured until 1915. The two patents, the pressed glass process and the brass socket were inventions patented by Enoch Robinson of Boston, who would continue to make a great impression in the hardware industry.

Post-1840 Builders’ Hardware

Between 1830 and 1860, the American builders’ hardware industry greatly improved its position to compete with imports. Their products became better suited for the American market, more competitive in pricing, and successful in overcoming the image of being inferior to imports.

The major development in the industry was the increased patenting of mortise latches and locks; these mechanisms operated by doorknobs soon gained favor over the longtime use of thumb latches for interior doors. Thumb latches would still remain in use for many years to come, delegated to service areas (i.e., the kitchen, the attic and storage areas), out of view from the public areas of a building.

The doorknob would find its place with surface-mounted latches, replacing the thumb press (above). Knobs for 1840-50s mortise latches and locks, included pressed glass and as the Nashua Lock Co. hardware pictured , were of polished cast brass and lacquered hardwood, in this case – rosewood.

The doorknob would find its place with surface-mounted latches, replacing the thumb press (above). Knobs for 1840-50s mortise latches and locks, included pressed glass and as the Nashua Lock Co. hardware pictured , were of polished cast brass and lacquered hardwood, in this case – rosewood.

Cast iron hinges became the norm, until about 1850, when the stamped plate hinges started to be produced. Wire nails and pointed wood screws became the builders’ fasteners of choice, particularly when used in the new balloon framing construction.

Then, during the 1840s and 1850s with new methods of shaping and molding doorknobs, less expensive but very attractive materials, (pressed glass, hardwood, clay or Argillo Stone, and porcelain) were used and became very popular. The knobs pictured here are pottery and milk glass knobs with the Robinson 1837 taped brass socket/shank.

By the 1860s, brown clay (misnomer “Bennington”), the swirl mineral, and porcelain doorknobs with simple cast iron shanks, first patented in 1841, became the norm of the time, particularly in rural houses and in the service areas of wealthy homes. They were the baseline items of hardware companies and catalog companies as Sears, Roebuck & Co. and Montgomery Ward well into the early twentieth century.

By the 1860s, brown clay (misnomer “Bennington”), the swirl mineral, and porcelain doorknobs with simple cast iron shanks, first patented in 1841, became the norm of the time, particularly in rural houses and in the service areas of wealthy homes. They were the baseline items of hardware companies and catalog companies as Sears, Roebuck & Co. and Montgomery Ward well into the early twentieth century.

Finally, there was the creation of the most attractive doorknob of the pre-1860 era on January 16, 1855, the “Boston silvered knob” or a.k.a. “mercury “ knob with its mirror finish. Its inventor, William Leighton of New England Glass in Cambridge, Massachusetts, proclaimed that his invention was a glass knob “which shall possess the color and luster, of polished silver, and at a cost little above that of the ordinary glass or porcelain knob.”

Finally, there was the creation of the most attractive doorknob of the pre-1860 era on January 16, 1855, the “Boston silvered knob” or a.k.a. “mercury “ knob with its mirror finish. Its inventor, William Leighton of New England Glass in Cambridge, Massachusetts, proclaimed that his invention was a glass knob “which shall possess the color and luster, of polished silver, and at a cost little above that of the ordinary glass or porcelain knob.”

The development of the American doorknob had worked its way from a relatively crude, heavy weight brass pastiche of its forebear to a well-constructed light-reflecting piece of art.

The American builders’ hardware industry had created products that were both technically refined and attractive.

With advent of the mortise latches and locks, doorknobs became not only a functional part of securing a door; their appearance took on a decorative importance. After the America Civil War, the concern for decoration would soar. During the Victorian age, a period of industrialization and mercantilism a perusing of ornamentation was carried to the ultimate. Doorknobs as any other domestic furnishing would reflect the tastes and styles in decorative art of the Victorian period in America.