Five years of practical work in the one-and-one-half acres of gardens have made her a firm believer in Buist’s words: “Try to love flowers–learn to cultivate them;–it will make you happier, it will make you better.”

Old gardens, like old houses, tell a story. Gardens created in the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century exhibited influences of past successes, concurrent innovations, and the social movements of the new republic. In the early 1800s, American nurserymen published practical gardening manuals that contributed significantly to the development of distinctively American gardens, first through suggesting choice, planting, and care of specimens, and later through careful design. Inspired by the ideals of the new republic, these horticultural professionals approached gardening democratically. They promoted the involvement of individuals of all social classes in creating and maintaining their own gardens, or suggested alternate forms of green spaces for those who possessed neither the space nor the means to create their own garden oases.

In early nineteenth century America, before the professionalization of landscape designing in the young country, nurserymen and seedsmen were among the horticultural elite. In addition to selling plants to the public, these men helped to found organizations that promoted horticulture in America. In catalogs, magazines, and garden manuals, they offered suggestions for planting and growing specimens and designing their placement, reveals garden historian Denise Otis in her book Grounds for Pleasure: Four Centuries of the American Garden. By making suggestions accessible to the American public, the nurserymen thereby reinforced the new country’s democratic principles and successfully initiated an American gardening tradition.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the gardening manuals of three men: Bernard McMahon, Robert Buist, and Andrew Jackson Downing, could be found on the library shelves of most literate Americans with gardening interests. The men skillfully adapted English practices to the American soil and climate and championed the incorporation of American specimens into the garden. Providing tailored practical gardening advice for the American environment encouraged experimentation with more costly ornamentals that during the colonial period were often overlooked for their lack of nutritional or medicinal value. At the same time Americans could enjoy creating beauty by including existing native specimens into their garden plan without incurring additional cost.

Bernard McMahon’s The American Gardener’s Calendar was first published in 1806. Divided into a functional and traditional month-by-month gardening guide format, McMahon’s manual was the first to consider the climate and soil of America’s different regions when suggesting appropriate specimens and offering growing advice. He endorsed native species, promoting the extended bloom time they afforded, as well as exotics.

Intending primarily to educate the majority of Americans about basic principles of a flower garden, such as placing smaller ornamentals at the front of a garden bed and larger behind, he sparingly suggested rigid design techniques. Unlike contemporary English landscape designers, he did not offer strict rules or diagrams for arranging beds or specimens, but rather recommended that the reader decide upon arrangement based upon his own abilities or needs. Furthermore, he outlined a variety of ancient and modern garden design techniques, advising readers to choose the elements that complemented the climate, soil, available space, and existing native specimens in their gardens, thus yielding unique creations.

Robert Buist championed the democratic American garden tradition begun by McMahon. In his three manuals The American Flower Garden Directory (1832), The Rose Manual (1844), and The Family Kitchen Gardener (1847), Buist aspired to involve the American public in a singular gardening experience that would sustain, comfort, and stimulate. He facilitated this connection by using simple wording and thoroughly explaining the growing process for his readers. In his capacity as nurseryman and to better serve amateur gardeners, he also personally tested the techniques he offered in his manuals. Like McMahon, Buist disregarded possible business profit by promoting the use of native specimens.

Robert Buist championed the democratic American garden tradition begun by McMahon. In his three manuals The American Flower Garden Directory (1832), The Rose Manual (1844), and The Family Kitchen Gardener (1847), Buist aspired to involve the American public in a singular gardening experience that would sustain, comfort, and stimulate. He facilitated this connection by using simple wording and thoroughly explaining the growing process for his readers. In his capacity as nurseryman and to better serve amateur gardeners, he also personally tested the techniques he offered in his manuals. Like McMahon, Buist disregarded possible business profit by promoting the use of native specimens.

Recommending garden bed and specimen placement to optimize sun exposure, ensure appropriate soil type, and to provide barriers from harsh weather, Buist, like McMahon, preferred practical design principles. Within a country striving to define and sustain itself, both nurserymen focused upon providing gardening essentials that would establish understanding and enthusiasm for gardening in the United States. Writing thirty years after McMahon, and in an increasingly sophisticated nation, however, Buist might have intensified rules of tasteful garden design. Instead, he emphasized design that complemented the beautiful natural landscape of America.

Furthermore, Buist’s desire to teach Americans to garden echoed the American Transcendentalists’ search for revelation through nature and embodied a reaction to the growing industrialization of America during the first half of the nineteenth century. Like New England Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, he recognized the presence of a higher power in the natural world, and hoped to share the spiritually uplifting experience of gardening with his readers.

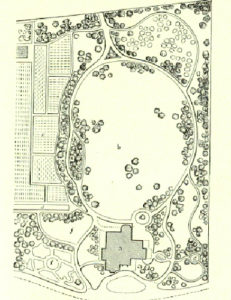

With the rise of industry in urban areas by the mid nineteenth century, nurseryman Andrew Jackson Downing capitalized on the movement of wealthier city dwellers to a rural environment. He envisioned the beautification of America through the creation of considerable naturalistic estates. However, Otis points out that while he wrote primarily for an elite class, Downing’s devotion to aesthetics and the proper care of an attractive landscape extended beyond the upper class. He hoped citizens across the nation would learn the rules of refinement he offered through his writing. His extremely popular The Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1841) appealed to varied classes of Americans, who practiced it to the best of their abilities and means.

In addition, Downing was among the first to promote an alternative natural refuge for those who remained in the urban industrial environment: the city park. Noticing the tendency of American city-dwellers to stroll and picnic within newly-established rural cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Boston and Laurel Hill in Philadelphia, Downing promoted the development of city parks to attract urban residents to a natural oasis within the city environment. Furthermore, his design ideas survived after his untimely death and were consequently incorporated within plans for suburban neighborhoods.

Today, many American gardens might highlight the growth of suburbia in the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth. Manicured lawns, house foundation plantings, and walkways carefully lined with annuals have become planting techniques that unify neighborhoods, while at the same time allowing freedom of expression. A look around our twenty-first century gardens reveals a mixture of current trends, evolving horticultural adaptations, and the traditions initiated by McMahon, Buist, and Downing. Even in suburbia, that ancient oak tree, persistent peony or antique rose might yield a more extensive story of America’s gardening past and its literary origins.

Michele Anstine is the director of the Read House and Gardens, a Federal period mansion complemented by mid-nineteenth century pleasure gardens. The gardens, attributed to nurseryman Robert Buist, inspired her investigation of Buist’s gardening manuals and others from the early nineteenth century.